Using the transistor base in here: transistor.

I’m gonna talk about logic gates and some basic possibilities like adders, subtractors, multipliers, and divisors. The main idea in these basic posts is to trace the way to assembly instructions and so on.

These logic gates are the lowest level we can reach in the hardware processing, obviously, these instructions alone don’t create anything really meaningful but the correct combination can create computer and processing machines of any type (except quantum computers but we’re not gonna talk about them today)

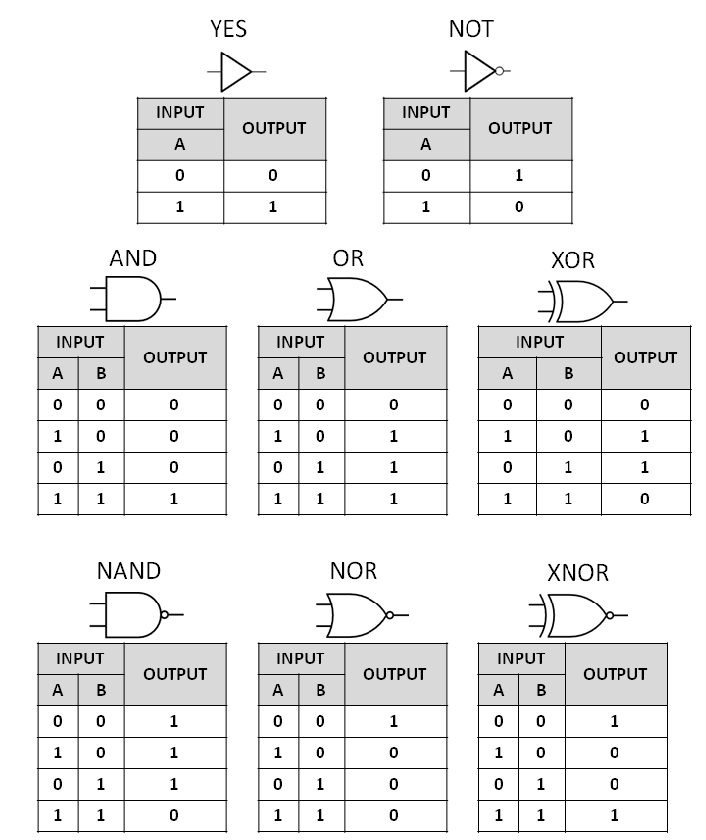

So logic gates are simply a transistor sequence that creates properties (AND, OR, NAND, NOR, XOR and XNOR)

- The X in the name means exclusively something, like in OR gate that usually would accept 1|1 but with X it’ll only accept the 1|0 (doesn’t matter the factor order)

- The N means the opposite of the original logic gate output.

- In the bottom of the image there are some “grounds” that i recommend looking in this explication before continuing

- The +6V is the place where electricity comes from and the out is where it comes out if the logic gate sustains the correct input (the input is just the electrical presence in A or B that’ll activate the transistor)

Transistor level approach:

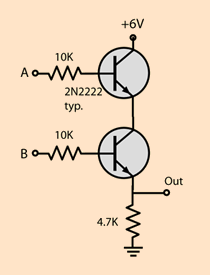

- AND (The first input and the second simultaneously):

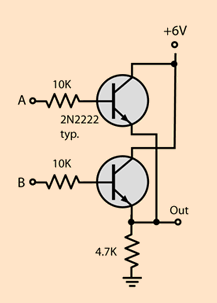

- OR (The first input, the second, or both):

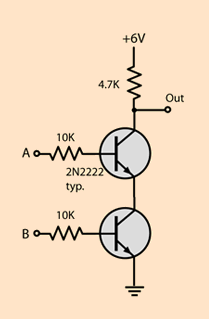

- NAND (The first input, the second, or none of them):

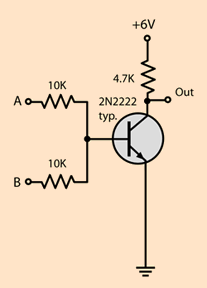

- NOR (Both of them off):

Truth tables:

I didn’t put XOR and XNOR transistor-level images because they use the other basic gates and i think it’ll confuse more than help right now.

Now you can be thinking something like:

-“Why would i even have to know this”

And i tell you that this is the base of any normal computer (quantum computer is the only different that i think rn but we’re not gonna talk about then today)

Now i’m gonna take a real approach for something more likely understandable, the adder:

Adder

- If you need some basic idea help in binary mathematics this site can help.

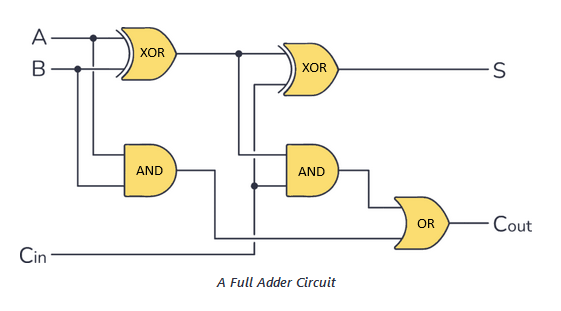

The adders use this logic gates setup (I’m gonna start using these images with de minimal representation of the logic gates because it would become bothersome to use so much space with logic gates at transistor level):

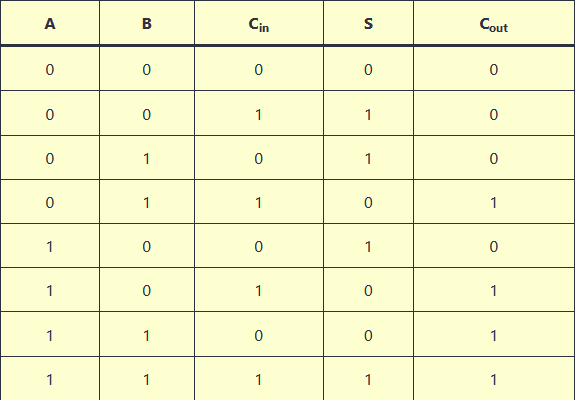

The adder receives 3 inputs, the binary of the first number, the second, and the “carry-in” (cin), but if it’s the first comparison the cin is ignored, because the carry-in is the carried number from the last operation, aka the COUT that appears at the end of the circuit, so for a better visualization this is the truth table:

So, if we have 2 numbers, 1001 and 1000 the adder circuit will compare the far right number from both this case it’ll be 1 and 0, resulting in S = 1 and Cout = 0, creating the first bit of the output that is S (1). With this, we conclude that the adder will be run for every bit we have in our sum operation, in this situation we have 2 numbers of 4 bits so the adder is gonna be run 4 times to get the full output/result.

If you want to see some real implementation of this adder there is this incredible video

Subtractor

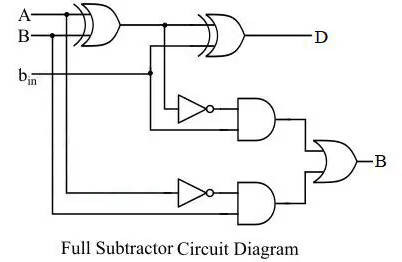

The subtractor uses the same base as the adder, but we have to think about some problems, for example, the negative numbers.

If we think straight the binary number technically groups just positive numbers, so the solution in this case is to use the MSB (most valuable bit) as a signal for positive (0) or negative(1), so if the number is positive like 1010 (10 in decimal) it would be 01010 and the opposite would be 11010 (-10 in decimal).

There are also two types of circuits for subtractors the full subtractor and half subtractor, they also apply for different situations, the “full” has 3 inputs so we can carry the the output of the last run and so on for more complex operations while the half is useful just for operations with 2 bits.

The logic circuit of the subtractor (the full because is more useful and interesting)

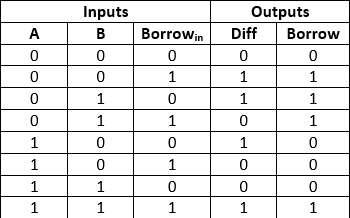

The truth table of the subtractor:

It’s important to highlight that there are also other ways to construct the logic gates in the circuit to get the same truth table (AKA.. do a subtractor in this case), so the purpose of the circuits is to return the expected outputs from the truth tables.

If you want to go deeper into the subtractors i recommend this site , because there are much more details that i ain’t going to tell here. After all, it would change the main topic.

Multiplier

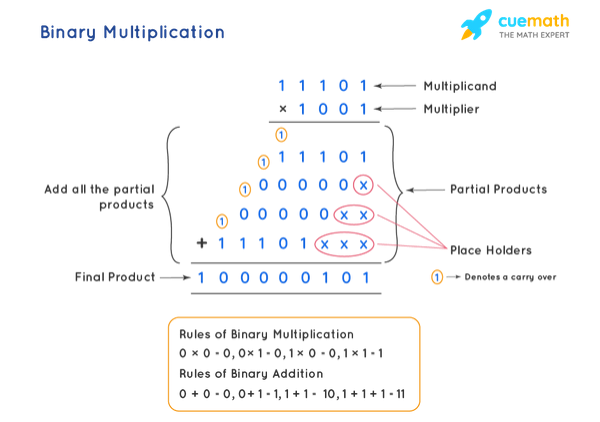

First things first, the multiplication consists of multiple comparisons between the multiplicand and the multiplier, and the number of runs of the circuit depends on the binary bit/byte “size”.

For example:

source

source

The comparison is made between each bit in the number and then we make a sum to resolve the problem, technically this is also the way to do multiplication in school but the number type is decimal besides the binary way.

Then we reach the complex part, the logic circuit because theoretically, we could just make the multiplicand sum itself times multiplier, but nothing is that simple and i’m gonna show just a basic resolution for now, and then in other posts, we’ll go deeper in how the ALU (part of the processor) actually make operations…

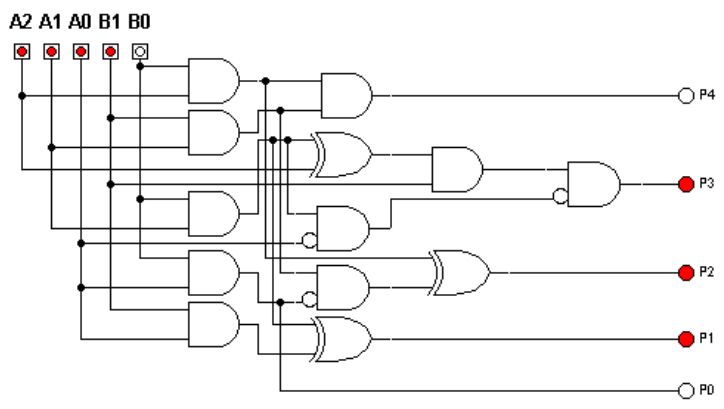

So continuing.. This is the logic circuit to multiplier with 2-bit numbers

And here is the truth table:

For each bit we have in the multiplication we got 2 more columns in the truth table and 2 more inputs/output, so in this setup things don’t escalate pretty well but it’s possible anyway

Divider

So for the last we have the divider that take other implications like numbers from the rational field, and this number until now wasn’t possible because we didn’t got any number different from a integer, and to solve this problem we could use floats (gonna talk more about in other post but the technical name of the integer problem would be underflow)

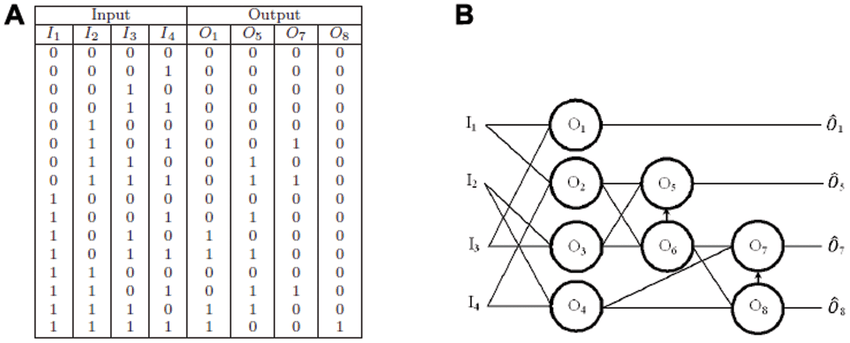

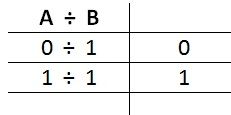

The truth table is the simplest of all:

Because if we think a little about we reach the conclusion that division by zero is meaningless

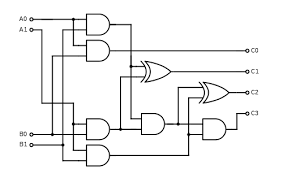

So to maintain the same schema of the multiplier, we are gonna use the 2 bit division:

It’s interesting btw that it’s necessary only AND and EX-OR logic gates..

The inputs are both 2-bit numbers and the output C’s are the quotient, so if we expose the output in some place we get the result (this is a simplified version of real-life utilization because for better approaches we probably would have to implement floating points and some other points and i think for now that this is enough)